Alex Pomeroy, Lancaster University.

In February 2025, I was contacted by Dr. Sunita Abraham of the Lancaster Black History Group and Lancaster University regarding a project initiated by Lancaster’s Mayor for 2024-25, Councillor Abi Mills, and Lancaster City Council. I would be working with Prof. Gordon Walker (acting as an advisor) from Lancaster University to research several items of historic furniture within the Town Hall collection.1

The principal aim of this research was to identify whether there were items of furniture in the Town Hall produced by the Lancaster-based firm Gillows & Co, in addition to those already part of public information about the Town Hall collection. This information would then be made into display boards, including information on any links to the firm’s involvement with the slave trade during Lancaster’s so-called ‘Golden Age’ during the 1700s and into the 1800s. Much of the Gillow’s furniture of the period was made from mahogany, and this colonial commodity is in some ways unique compared to many of the other products of enslaved labour. Unlike sugar, rum, dyes, rice and tobacco, it is not a consumable product and can still be seen today as a tangible product of the enslavement of millions of people. After further investigation, we found three pieces of historic furniture: a sideboard and also a set of table and chairs from the early nineteenth-century and a nineteenth-century cabinet. Two of these pieces were certainly manufactured by Gillows, and whilst we have not been able to definitively confirm the provenance of the third, it is possible that it was at the very least designed using Gillows’ sketch books. The history of each piece will be discussed in depth in this article.

For me, the most interesting development from this research has been the process of unravelling Gillows’ indirect associations with transatlantic slavery via their purchase of mahogany and other woods for making furniture, alongside their mercantile interests in trading sugar and rum during the eighteenth century. We approached this subject by studying the history of the Gillows family and their business, the wider connections between mahogany farming and transatlantic slavery, then finally the three items of furniture we identified within the Town Hall. This blog has been structured in the same way: to provide the context of the Gillows’ business and the materials they used to enable readers to think critically about the histories behind the surviving furniture and how we present such objects to the public.

Gillows & Co, or any persons involved within the firm’s hierarchy, may not have traded directly in human beings prior to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834.2 However, their story stands as an important reminder of how indirect links to transatlantic slavery permeated unexpected corners of British society during the ‘long eighteenth century’ (c.1688-1815), and how, locally, such trade regenerated the built environment around Lancaster.3

Gillows & Co, 1730-1990 – A Potted History.

Robert Gillow (1704-1772) was born in the parish of Singleton, around twenty miles south of Lancaster, in 1704 to Richard Gillow and Alice Swarbrick.4 He served as an apprentice cabinet maker in his youth with John Robinson, a Lancaster-based joiner, before being made a freeman of Lancaster c.1727-28.5 Freeman status granted Robert the right, amongst other things, to vote, own property within the town boundaries, and trade goods.

Gillows & Co. was established by Robert Gillow a couple of years later, in 1730, at a time of major rebuilding in Lancaster which increased the demand for new furniture and household fittings. Britain was the largest consumer of mahogany during the eighteenth century, it was in particularly high demand due to its deep colours, durability and fine grain patterns. Following the abolition of import tax on hardwoods in 1720, it also became more affordable to import from the Caribbean. Lancaster aligned with these national trends, and mahogany featured heavily in many of Gillows’ earliest designs.6

In 1757, Robert Gillow partnered with his son, Richard, and the business became known as ‘Robert Gillow & Son’. Aside from his work with the furniture company, Richard also left his mark in local Lancastrian history as the designer of several prominent pieces of Georgian architecture which still stand in town today. The most notable of these works was the Customs House on St. George’s Quay, designed in 1764 and now the home of the Lancaster Maritime Museum. It is also likely that he designed the firm’s offices and workshop, now a set of flats, at No.1, Castle Hill, in June 1770.7 Elsewhere, their warehouse on Cable Street (now converted into student accommodation) stands as a prominent reminder of Gillows’ once-large presence in the Lancaster economy.

No.1 Castle Hill, designed by Richard Gillow and opened in 1770, these premises were Gillows’ warehouse and workshop until 1882.

The Customs House, now the Lancaster Maritime Museum, on St. George’s Quay. Opened in 1764 to Richard Gillow’s design. By a quirk of fate, the building was also in continual use until 1882 when the Customs duties were transferred north to Barrow-in-Furness.

Gillows’ 1881-built showroom on North Road, Lancaster. Behind this complex is their 1878-built factory on St. Leonard’s Gate, both sites are now large blocks of student accommodation.

Following their continued growth, Gillows opened a showroom in London (c.1769-70) on Oxford Street. This was during a period of transformation from a residential area to the bustling retail centre that Oxford Street is known for today, which exemplified the status of Gillows’ furniture as the century progressed.8 By the time of Robert Gillow’s death in 1772, their furniture garnered a truly global market, with trade stretching across the British Empire. As early as 1742, Gillows were creating furniture for export to the Caribbean and the opening of the London showroom was a marker of their ‘meteoric rise’ in the furniture world.9 Their success continued through to 1800, despite the disruption caused by the Seven Years War (1756-1763) and the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The latter conflict brought trade to a standstill and the prices of luxury woods soared before trade boomed once more in the mid-1780s. Between 1784 and 1790, £900,000 worth of mahogany (or 124,000 tons) was imported from the colony of Jamaica alone, such a boom was completely unsustainable and caused deforestation across large parts of Jamaica.10

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the poor economic climate had led to higher taxes and import prices for luxury woods. Coupled with the economic strain, the three Gillow sons who had inherited the business only had one son between them to pass it onto. Therefore, beginning in 1813, the firm was sold in instalments to the partnership of Leonard Redmayne, Whiteside and Ferguson.11

The new partners retained the Gillow name and oversaw the expansion of the company into interior design alongside furniture building. At the end of the nineteenth century, financial difficulties again caused issues amongst the Gillows & Co. hierarchy. A loose financial agreement began with Liverpool-based cabinet makers S.J Waring & Sons in c.1897, and by 1903 the establishment of a merger to form Waring & Gillow was completed. Despite their financial difficulties, Waring & Gillow remained one of the few employers of skilled labour in Lancaster by the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, as the town’s dominant industries (linoleum and oilcloth manufacturing) required largely unskilled labour.12

Gillows enjoyed something of a renaissance in the early twentieth century, which led to the opening of new stores in Paris, Madrid, and Brussels. Waring & Gillow found further success in designing interiors for ocean liners, including the ill-fated RMS Lusitania (1907) and the RMS Queen Mary (1934). 13 However, the firm found themselves in decline during the second half of the twentieth century and the Lancaster branch finally closed in 1962. In 1980, another takeover by Maple & Co. led to the creation of Maple, Waring and Gillow before the Gillows name finally disappeared in 1990 as the Allied Maple Group amalgamated their businesses, ending 260 years of Lancastrian history.14

Mahogany Logging, Gillows and Indirect Participation in the Transatlantic Trade.

In 1808, Gillows offered prospective buyers a catalogue of 72 differing types of ‘curious wood’. Many of them, such as English Ash, English Beech and English Oak, came from domestic species of British tree. Some types were sourced even more locally to Lancaster, so much so that the 1808 catalogue offered sections of English Oak which had been salvaged from the old gates of Lancaster Castle. The real value in Gillows’ services, however, came from the exotic and luxury wood types which they could provide from across the globe. The 1808 list stands as a testament to the extensive trading network that the Gillow family had developed across the eighteenth century. The name of each wood alone betrayed their exotic origins: East India Yew, Jamaica Stainwood, Gambia Wood, Italian Walnut, Novia Scotia Wood and, of course, mahogany. Specifically, ‘Spanish Mahogany’.15

Today, the sustainability of such produce is ensured by certification granted by organisations such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), despite ongoing pressure to illegalise mahogany logging due to human rights abuses and environmental damage. 16 Throughout the ‘long eighteenth century’, however, the logging wood for luxury furniture in the Caribbean and Latin America was a further example of colonial exploitation of enslaved labour.

Mahogany was particularly sought after due to its rich colour, finely patterned grain and weight; exploiting it as a commodity of colonialism was inextricably linked to slavery. Indeed, the roots of the word ‘mahogany’ may lie within the Nigerian word M’Oganwo, used by enslaved Africans who saw similarities between mahogany and a native African tree, which was then picked up by their European overseers. 17 Mahogany had first been used in the late seventeenth century, although not as a luxury material but as a form of ballast for shipments of logwood (which is not actually wood, but a rich dye produced from shrubby, tree-like plants native to the same areas as mahogany). It began to gather popularity amongst British cabinet makers, including the young Robert Gillow, in the 1720s when the boom developed into what was known as ‘mahogany mania’ by the mid-eighteenth century.18

Jamaica became the principal source of mahogany from c.1750 and stayed so over following decades until it became largely deforested by the early 1800s. During this period, as much as 90% of the population were enslaved. 19 The island had been a British colonial possession since the 1660s after various battles to seize control from the prior colonial power in the region, Spain. Since then, it had been ruled by a white settler elite who exerted extreme amounts of ‘privilege and terror’ over the enslaved population to extract as much wealth from the island’s resources as possible.20 Whilst colonial Jamaica is most closely associated with the production of sugar and rum, mahogany was also a large part of the island’s economy. The process of logging, cutting and packing mahogany planks was all undertaken by enslaved labour, which was incredibly arduous and dangerous work in a gruelling tropical climate. Enslaved people would carry out such work in ‘gangs’, overseen by a driver who enforced brutal punishment whenever possible. In 1824, Thomas Cooper wrote Facts Illustrative of the condition of the Negro Slave in Jamaica with Notes and an Appendix. Inside, he captured the essence of the endemic violence in Caribbean colonies which drove the production of mahogany and other such goods:

The gangs always work before the whip, which is a very weighty and powerful instrument. The driver has it always in his hand, and drives the Negroes, men and women without distinction, as he would drive horses or cattle in a team. Mr. Cooper does not say that he is always using the whip, but it is known to be always present, and ready to be applied to the back or shoulders of any who flag at their work, or lag behind in line.21

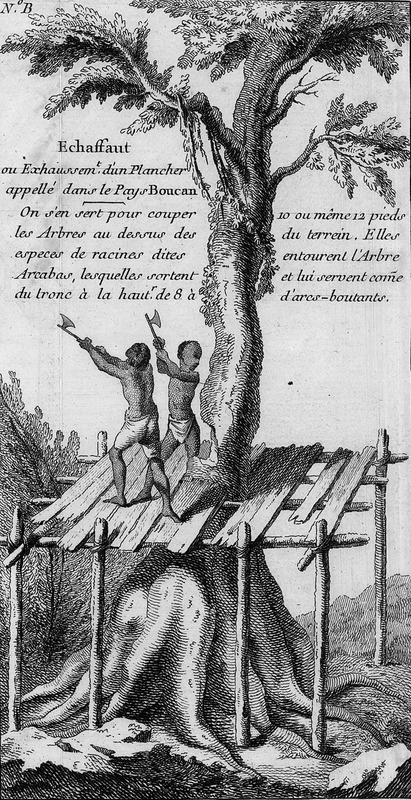

‘Felling a Tree, Cayenne (French Guiana), 1763’.

‘Sawing Wood Planks, Brazil, 1816-1831’.

Though neither are examples from Jamaica, these two images show the process of cutting down trees and then preparing the individual planks for shipment, usually to Europe, undertaken by gangs of slaves.

Both images can be found on the ‘Slavery Images’ online database: https://www.slaveryimages.org/database/image-result.php?objectid=206 & https://www.slaveryimages.org/database/image-result.php?objectid=257 [Accessed 1 May 2025].

The ‘mahogany boom’ in Jamaica coincided with Lancaster’s own boom during the mid-eighteenth century as the once sleepy port became the fourth largest in England dealing in the transatlantic trade, behind London, Liverpool and Bristol. It is worth noting, however, that although Lancaster was the fourth largest transatlantic port in England, the number of slaving voyages and enslaved people that can be attributed to this city puts it a long way behind the other three cities (all of which were much larger) when this listing is considered in relative terms. In 1698, a visitor to Lancaster commented that it was ‘old and much decay’d [sic] […] the town seems not to be much in trade as some others’.22 A century later, the town had developed into a modern and bustling port, which in turn financed the rebuilding of much of Lancaster to reflect the styles and wealth of Georgian England.

This, in turn, enabled many local industries to develop and grow their trade – including Brockbank’s shipyard, numerous sailcloth manufacturers, and, of course, Gillows’ business. It is important to clarify here that the Gillow family and their business had strictly limited involvement in the direct trade of enslaved people. Robert Gillow was a minor shareholder (one twelfth) in The Gambia, which made two transatlantic voyages in 1755 and 1756, which ‘was not a financially successful or significant investment’.23 Though its cargo of ‘62 casks sugar, 31 puncheons rum, 26 bags cotton, 8 tons logwood, 41 bags ginger’ demonstrated how Gillow was investing in the most infamous of slave-produced goods. The continued demand for high-quality Gillows’ furniture ensured their presence in the exploitative mahogany trade, so much so that they frequently complained to their agents in the West Indies for failing to source enough mahogany to supply the rampant demand. Records of Lancaster-bound ships leaving Jamaica from 1747-1786 frequently cited large amounts of the luxurious wood. Expedition set sail in 1747 with ‘2,500 feet mahogany, 12 tons wood’, Barlborough contained 40 tons of mahogany seven years later, Norfolk made a return voyage in 1765 with 413 planks and Fenton ferried a further 541 planks in 1785.24

The appetite for Jamaican mahogany was such that by the end of the eighteenth century, the island had been practically stripped of its natural resources due to a combination of over-farming and the slow growth of freshly-planted trees. This led merchants and cabinet makers like Gillows to look for alternate sources of supply within the region. Belize (known as ‘British Honduras’ until 1973; independence came in 1981), Honduras (or ‘Spanish Honduras’ prior to independence in 1821) and Santo Domingo (the capital of the present-day Dominican Republic) became the principal exporters of logwood and mahogany in the early decades of the nineteenth century.25

Aside from benefitting from the product of enslaved labour, Gillows also profited from settlers in the Caribbean who could afford such luxury furniture thanks to the wealth they had accumulated. Between 1744 and 1796, fifty-six vessels sailed to various locations in the Caribbean with items of Gillows’ goods on board, some of which was for colonial officials who would have overseen the running of plantation society. 26 Their connections to the Caribbean were no doubt aided by Gillows’ close relationships with many prominent Lancaster-based merchant families, including the Rawlinsons, Hindes and Satterthwaites, who were all involved either in the slave trade or owned their own slaves.27

Thus, whilst we must not brashly condemn the Gillow family as ‘slave traders’, it must be considered that the materials they used to make the furniture which made them a household name in eighteenth-century Britain was only available in such quantities due to systems of chattel slavery. Furthermore, the wealth generated within the Caribbean colonies enabled many settlers and their families to purchase luxury items for their own homes to exhibit their wealth and status, which created more business for Gillows as a manufacturer of a luxury product. One of the finest surviving pieces of eighteenth-century Gillows’ furniture is a bookcase/cabinet produced in 1772 for Mary Hutton Rawlinson, the widow of the Quaker merchant Thomas Hutton Rawlinson. Thomas’ sons, John and Abraham, were also prominent traders of sugar, rum, cotton, coffee and mahogany for Gillows.28 The family’s wealth, therefore, was intimately connected to the exploitation of enslaved people. Today the Rawlinson’s cabinet is on display at Lancaster’s Judges’ Lodgings Museum and a recent decolonisation initiative has led to new labels being displayed alongside their Gillows’ collection to explain their history with transatlantic slavery. However, one wonders how many other such pieces are still bought and sold for large sums at antique auctions without consideration to the materials used in their creation.

Furniture within Lancaster Town Hall.

The original aim of this research was to identify eighteenth century items of Gillows furniture currently held within the collection at Lancaster Town Hall, which opened in 1909. Though the building dates from the twentieth century, it contains many earlier items of furniture which were originally used at the earlier Town Hall (Lancaster has had several throughout history) which was completed in 1783 and is now home to the Lancaster City Museum. Sadly, no definitive inventory exists that would catalogue either the furniture which was held at the previous Town Hall or pieces that are now used at the current site. In lieu of this, we made several trips to the current Town Hall to investigate the wealth of furniture in the building, and the three pieces below were found to have the closest connections to Gillows.

Sideboard Manufactured by Gillows & Co. of Lancaster, c.1828-38.

This ‘pedestal end’ sideboard was likely manufactured by ‘Gillows’ around 1828-1838, after the sale of the business out of the Gillows family into the possession of Redmayne, Whiteside and Ferguson and during the era of British abolition (1833). Although it does not bear a definitive mark, we can safely assume it was made by Gillows due to the similarities it bears to another pedestal end sideboard they made for Thomas Parr Esq. of Grappenhall Heys (Warrington) in June 1828, identified through research conducted by Susan Stuart.29 The Parr table cost £40, or £3,552 in today’s money. This table was likely even more expensive as it is features much more intricate carving than the Parr piece, however the original order invoice sadly seems lost to time. Sadly, this piece has been damaged over time, as the pictures below show, with several sections of the carving missing.

The sideboard was crafted from mahogany, likely sourced from Spanish Honduras, British Honduras or St Domingo (as then named) in the Caribbean. Jamaica had previously been the preferred source of mahogany for Gillows, but this had been largely cleared or stripped out of its forests by the late-eighteenth century due to the booming demand. Although dating from late in the period of the slave trade, the logging, transport and preparation of mahogany for this sideboard may have still relied on enslaved labour for the work involved.

D-End ‘Pillar and Claw’ Table & Chairs, c.1810-1820.

The table is known as a ‘D end’ example, due to the shape of the two halves, and it should feature another centre section to extend the table for larger parties once the halves are separated, however this is sadly missing. The distinctive shape of the legs gained the nickname ‘pillar and claw’, and Gillows first used this style on a similar table made for William Hasell of Penrith in 1774. Gillows made a much larger ‘pillar and claw’ table in 1798 for Eglinton Castle in Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, whilst the accompanying chairs bear a close resemblance to a pattern sold by Gillows in 1806.

It is possible that this set was made by Gillows, however it is not marked in any way. Whilst the mark may have been stamped onto the missing centre section, it is also possible that one of Gillows’ ‘journeymen’ (apprentices) made this for another company after having access to Gillows’ design and sketch books, which was common practice during the period. Gillows were different from other major furniture makers of their era, such as Hepplewhite or Chippendale, in that they never published a book of designs.30 Therefore, the only people with access to Gillows designs were the journeymen and apprentices employed by the firm.

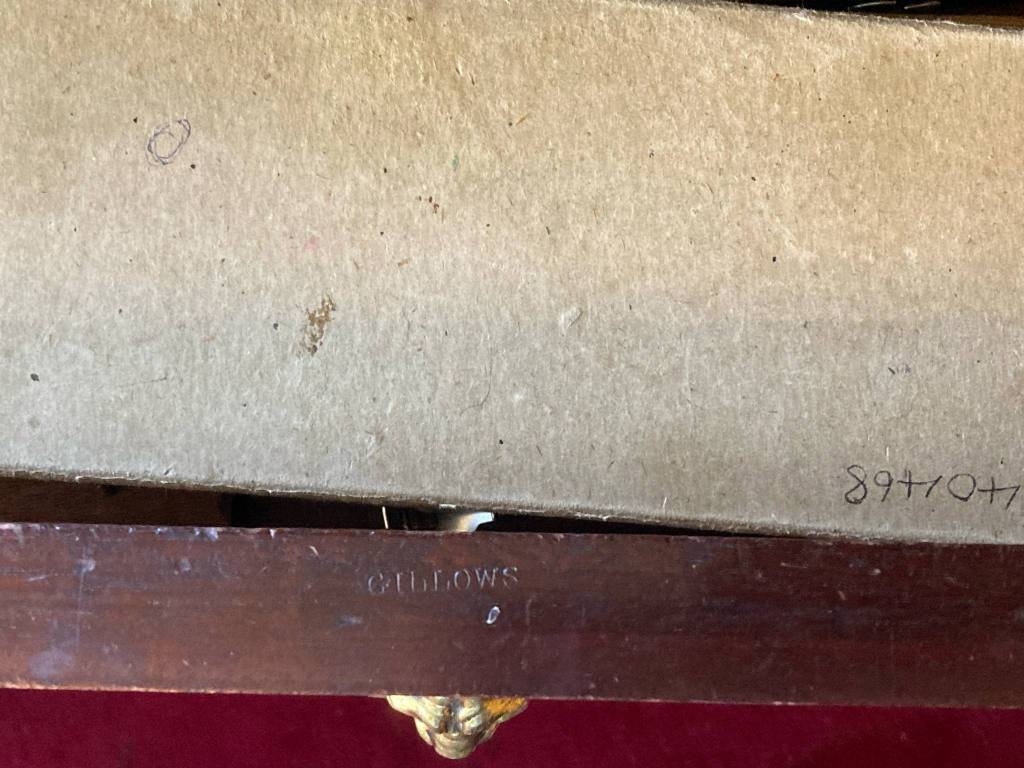

Cabinet Manufactured by Gillows & Co. of Lancaster, c. late-1800s

This cabinet bears a later-nineteenth century GILLOWS stamp, though it may be from the period of the firm’s merger with Waring of Liverpool to become Waring & Gillow (c.1897-1903). Up-to-date stamps and marks were inconsistently applied throughout the firm’s existence, and Gillows only started marking furniture at all in 1770 after forty years of trading. 31 The furniture constructed in this later period was not as finely crafted as those from the eighteenth and early-nineteenth century. In later years, Gillows frequently referred to earlier design and sketch books as eighteenth-century styles and designs remained fashionable well into the early 1900s. This particular cabinet appears to have been made in the style of a much finer piece made by Gillows for the Rawlinson merchant family in 1772. Described by the Regional Furniture Society as ‘a provincial masterpiece’, this elaborate secretaire bookcase was purchased for the nation in 2007 and is now on public display within Lancaster’s Judges’ Lodgings. Later furniture such as the Town Hall’s cabinet helps to demonstrate how the wealth and style associated with Lancaster’s ‘Golden Age’ as a bustling eighteenth-century port involved in the transatlantic slave trade far outlasted the period itself.

Conclusion – How is this still relevant today?

The purpose of this research was never to assign ‘guilt’ to Gillows as a firm or to the individual family members who ensured their success throughout the eighteenth century. It must be remembered, in the words of Melinda Elder and Susan Stuart, that Robert Gillow was very much ‘a man of his times’ when it comes to his relationship and connections to transatlantic slavery.32 The Gillow family were not slave traders themselves, this much is true. However, their mercantile interests in the trade of sugar and rum, alongside their extensive use of slave-farmed mahogany and their selling of completed furniture to wealthy settlers in the Caribbean enabled them to profit from the wealth of those directly associated with the trade and exploitation of human beings. Today, eighteenth century Gillows’ furniture can be valued at hundreds of thousands of pounds by auctioneers, such is its quality. For example, the bookcase/cabinet manufactured by Gillows for the Rawlinson family in 1772 fetched £260,000 when it was bought for the nation in 2007.33 Furthermore, later-made pieces such as the cabinet in the Town Hall were designed in eighteenth-century styles to recall a romanticised ‘Golden Age’ of British (and Lancastrian) society which whitewashed the exploitation on which much of it was built. Gillows’ indirect associations with transatlantic slavery should not consign surviving items of furniture to the bin. Rather, they should provoke critical conversations regarding the origins of luxury goods from the period to develop our understandings of how British involvement in transatlantic slavery influenced society.

Furthermore, analyses of historical slavery and the ways in which industries and individuals benefitted from exploitation throughout the eighteenth century and beyond should allow us to think critically about modern society, how and where we source products, and how we can eliminate exploitative practices today. According to their latest figures from 2022, Anti-Slavery International has estimated that 49.6 million people live in a state of slavery around the globe today, a quarter of whom are children and over half of the total figure are trapped in systems of forced labour. 34 The 2022 figure vastly outnumbers the most common estimates amongst historians for the total number of people trafficked during the period of transatlantic slavery (1500-1800), which is usually taken to have been from between 12-15 million people.35 These figures help put into perspective the value of this research, not only as a piece of historical inquiry, but as a way of utilising the lessons of the past to improve both the present and the future.

Acknowledgements

This project was possible due to the help and expertise of several people. My thanks go to Dr. Sunita Abraham, Professor Gordon Walker, Councillor Abi Mills, the Mayor of Lancaster for 2024-25, and Councillor Sam Riches for creating the opportunity for such research within the Town Hall to take place. I am also grateful to the mayor’s beadle, Chris Clifford, for showing us around the Town Hall and sharing his expertise on its history. Finally, my thanks also go to Susan Stuart for her invaluable insights into the history of Gillows and its furniture and for her comments on the provenance of the featured pieces at the Town Hall. All other interpretations and points made are strictly those of the author alone.

Notes

1 This research would have been much more difficult had it not also been for the extensive work conducted by Susan Stuart on the history of Gillows and the surviving items of furniture they produced.

2 Members of the family did, however, own shares in vessels participating in the transatlantic trade, this will be discussed in full further on. However, for further reading, see: Melinda Elder and Susan Stuart, ‘Were the Gillows of Lancaster Slave Traders?’, Contrebis, Vol.39 (2021), pp.20-8.

3 The phrase ‘long eighteenth century’ is typically used by historians studying the period from the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Though these dates are not universally agreed upon, the period is expanded beyond a century to cover the rapid social, political and technological transformations across Britain and Europe. For an overview of the theory, I recommend: Daniel M. Abramson, ‘History: The Long Eighteenth Century’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 64.4 (2005), pp.419-21.

4 ‘Gillow Family Tree’, Gillow Genealogy – Keith Gillow’s Home Page, https://people.maths.ox.ac.uk/gillow/genealogy/tree/3a.shtml [Accessed 16 April 2025].

5 Susan Stuart, ‘Gillows Family (per c.1730 – c.1830)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, < https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.lancs.ac.uk/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-67318?rskey=SWbhVM&result=3#odnb-9780198614128-e-67318-headword-2> [Accessed 2 May 2025].

6 Susan Stuart, Gillows of Lancaster and London, 1730-1840: Cabinetmakers and International Merchants: A Furniture and Business History (ACC Art Books, 2008), Vol. I, pp.25-6.

7 ‘1 Castle Hill’, Historic England, < https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1220647?section=official-list-entry> [Accessed 29 April 2025].

8 Ben Weinreb et al, The London Encyclopaedia (Pan Macmillan, 2008), p.611.

9 Adam Bowett, ‘The English Mahogany Trade 1700-1783’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Brunel University, 1996), pp.59-60 https://bnu.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/9639/1/361085.pdf [Accessed 30 April 2025].

10 Ibid, pp.126-32.

11 For further information on Redmayne, Whiteside and Ferguson, see: ‘Gillow (1730-1840)’, The Furniture History Society – BIFMO, https://bifmo.furniturehistorysociety.org/entry/gillow-1730-1840 [Accessed 30 April 2025].

12 Elizabeth Roberts, ‘Working-Class Standards of Living in Barrow and Lancaster, 1890-1914’, Economic History Review, Vol. 30, No. 2 (1977), pp.306-21 (p.307).

13 ‘Waring & Gillow and the RMS Lusitania’, Lancashire County Council, https://lancashiremuseumsstories.wordpress.com/2021/10/15/waring-gillow-and-the-rms-lusitania/ [Accessed 1 May 2025].

14 Judith Dunn, ‘Gillows of Lancaster: Two Centuries of English Furniture’, New England Antiques Journal, https://web.archive.org/web/20120218212434/http://www.antiquesjournal.com/Pages04/Monthly_pages/nov08/gillows.html#topofpage [Accessed 2 May 2025].

15 For a copy of the 1808 catalogue, see: Stuart, Gillows of Lancaster and London, p.141.

16 Gordon Walker and Brontë Crawford, ‘Mahogany: A historical geography of a lasting commodity of 18th century enslavement’, Geography, 109.3 (2024), pp.163-8 (p.167).

17 Jennifer L. Anderson, ‘The Atlantic Mahogany Trade and the Commodification of Nature in the Eighteenth Century’, Early American Studies, 2.1 (2004), pp.47-80 (p.60)

18 Ibid, p.49, and Walker and Crawford, ‘Mahogany’, p.164.

19 Walker and Crawford, ‘Mahogany’, p.164.

20 Michele Lemonius, ‘“Deviously Ingenious”: British Colonialism in Jamaica’, Peace Research, 49.2 (2017), pp.79-103 (p.80).

21 Thomas Cooper, Facts Illustrative of the condition of the Negro Slave in Jamaica with Notes and an Appendix (J. Hatchard & Son, 1824), p.11. Available at: https://www.recoveredhistories.org/browse/binns-vol-031-007/?cpage=1 {Accessed 1 May 2025].

22 Melinda Elder, The Slave Trade and the Economic Development of Eighteenth Century Lancaster (Ryburn Publishing, 1992), p.13.

23 See: Walker and Crawford, ‘Mahogany’, p.166, and Melinda Elder and Susan Stuart, ‘Were the Gillows of Lancaster Slave Traders?’, Contrebis, Vol.39 (2021), pp.20-8 (pp.22-6).

24 For Gillow’s complaints to their agents, as well as further shipping records, see: Elder, The Slave Trade, pp.96-9.

25 See: Craig S. Revels, ‘Concessions, Conflict and the Rebirth of the Honduran Mahogany Trade’, Journal of Latin American Geography, 2.1 (2007), pp.1-17.

26 Walker and Crawford, ‘Mahogany’, p.166.

27 Ibid, p.166.

28 Melinda Elder, ‘A Georgian Merchant’s House in Lancaster: John Rawlinson, A West Indies Trader and Gillows Client’, Contrebis, 38 (2020), pp.3-14 (p.10).

29 Susan Stuart, Gillows of Lancaster and London, 1730-1840: Cabinetmakers and International Merchants: A Furniture and Business History (ACC Art Books, 2008), Vol. I, p.326. Parr was a member of the Parr banking family, one of NatWest’s forerunners. In an interesting twist of fate, another of NatWest’s predecessors had ties to Gillows’ company. Leonard Redmayne was the inaugural chairman of the Lancaster Banking Company in 1826 whilst also serving as one of Gillows’ senior partners and held the position until 1860. Redmayne’s company eventually became part of NatWest, and their Lancaster branch on Church Street occupies the original Lancaster Banking Company building today.

30 Lindsay Baynton, Gillow Furniture Designs, 1760-1800 (Bloomfield Press, 1995), p.15.

31 Susan Stuart, ‘A Survey of Marks, Labels, and Stamps used on Gillow and Waring & Gillow Furniture 1770-1960’, Regional Furniture, Vol.12 (1998), pp.58-93 (p.58).

32 Elder and Stuart, ‘Were the Gillows of Lancaster Slave Traders?’, p.26.

33 ‘Gillows of Lancaster – Lancaster Civic Society Leaflet 5’, Lancaster Civic Society, https://www.lancastervision.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/5-Gillows-of-Lancaster-Logo.pdf [Accessed 30 April 2025].

34 ‘What is modern slavery?’, Anti-Slavery International, https://www.antislavery.org/slavery-today/modern-slavery/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20latest%20Global,of%20modern%20slavery%20are%20children [Accessed 29 April 2025].

35 Ewelina U. Ochab, ‘The Transatlantic Slave Trade and The Modern Day Slavery’, Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ewelinaochab/2019/03/23/the-transatlantic-slave-trade-and-the-modern-day-slavery/ [Accessed 29 April 2025].

Leave a comment