This is a photograph of Malena and Temi, both pupils at a local school, participating in a Black Lives Matter Protest on the steps of the Town Hall in Dalton Square, Lancaster, in June 2020. The photograph was taken by their friend, my 17-year old daughter, Bella, and is published here with permission.

Tracing Threads of Connection

Alongside the Victorian Town Hall, (for more on Lancaster Town Hall and its history see my recent book Stigma), Dalton Square is filled with fine Georgian Houses. Unbeknownst to these young Black Lives Matter protestors in 2020, in the 19th century, Dalton Square was home to a significant beneficiary from plantation slavery, John Bond (1778 – 1856), who lived at what was then number 1 Dalton Square, and was twice Mayor of the town. John Bond inherited his Dalton Square house, along with Yealand Hall (in Carnforth), and 18 shares in the Lancaster Canal, from his uncle Thomas Bond (1758 – 1817). He also inherited property and plantations in the West Indies, including around 700 enslaved people in Demerara (now part of Guyana) and Grenada. (The 1817 will of Thomas Bond detailing his property and beneficiaries, is held in the Lancashire Archives).

Along with involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, in the 17th and 18th centuries Lancaster was heavily involved in trading with the West Indies and Americas. Lancaster traders and merchants developed extensive commercial networks, importing goods produced by enslaved people, such as mahogany, sugar, dyes, spices, coffee and rum, and, later, cotton for Lancashire’s mills, from plantations. They also exported fine furniture, gunpowder, woollen and cotton garments. Young men from Lancaster families worked as agents and factors across the West-Indies. This gave rise to new wealth and power in the town. As Eric Williams details in Capitalism and Slavery (1944), slave traders, and West-India’s merchants and their descendants dominated local political life in towns such as Lancaster, and cities such as Liverpool and Bristol, ‘as aldermen, mayors and councillors’. Over generations some of these families accumulated land and property, including plantations and enslaved people, in overseas colonies. Some who inherited overseas property (and people) didn’t want to travel themselves, preferring lives as gentlemen “at home”. These absentee landlords sought out young men seeking opportunities and sent them overseas to work as overseers and managers on their plantations and estates.

In this blog post I will explore some of Lancaster’s connections with cotton and sugar plantations in Guyana in South America. While on the American mainland, this country is ordinarily understood as part of the Caribbean. Before colonisation by Europeans it was populated several tribes of indigenous peoples, those who survived are today known collectively as Amerindians. Guyana was a Dutch colony (from the 16th century) made up of three main regions, Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo. These regions came under fully under British control in 1796, and were folded together to form the colony of British Guiana in 1831. While it was formally a Dutch colony, British merchants, planters, and traders had been present in Guyana from at least the early part of the 18th century. When the British took formal control of the colony in the late 18th and early 19th century, it was rapidly developed into a major sugar producer, creating fortunes for those who owned plantations and slaves there. As Nick Draper notes on the new “planter class” this wealth created “a startlingly high proportion of absentee slave owners in British Guiana were among the very richest men and women of their time, and many had reached that level of wealth in their own lifetime”.

The wealth that poured into Britain from Guyana wasn’t only a consequence of sugar, but also of tax-funded compensation for manumission.

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 ‘formally freed 800,000 Africans who were then the legal property of Britain’s slave owners’. Many people, including Lancaster’s John Bond, became millionaires overnight, when the British Government legislated that taxpayers would compensate this already wealthy group of aristocrats, landowners and middle-class inheritors for the loss of their human property on overseas plantations. Further, a decision was made by the British government (who where petitioned by Guyanese slave owners) to award compensation based the local “market value” of enslaved people in each colony. Due to a shortage of enslaved labour in Guyana where “mortality rates were exceptionally high in these territories”, those who owned enslaved people in Guyana were more handsomely compensated than those who owned people in other colonies, such as Jamaica. In short, enslaved people in Guyana had a bigger price tag on their heads.

Indeed, while the slave trade had been formally abolished in Britain and her colonies in 1807, in order to meet market demand for enslaved labour in newer colonies like Guyana, which were “taking off” in terms of sugar production at the beginning of the 19th, the trade in enslaved people remained buoyant across the British Caribbean.

While we tend to mean the slave trade to refer to the capture and kidnap of people in West Africa and trafficking across the Atlantic, trading in enslaved people as chattel (property) continued in the West Indies. For example, should trade in enslaved people between slave owners on plantations was commonplace, as were associated practices of “renting out” chain gangs of enslaved people, and “mortgaging” enslaved people to raise revenue.

Details of the huge windfall, (the equivalent of approximately £2 million pounds today) received by Lancaster’s John Bond as compensation for the freedom of the enslaved people he had inherited from his uncle, can be tracked on the British Legacies of Slave-Ownership database.

“The slave owners received compensation, interest on the compensation payments from 1 August 1834, and a further period of forced labor under apprenticeship. In addition, of course, the estate owners held on to their land and had the opportunity to work it with free labor or, indeed, indentured labor. ”

Nick Draper

In total a £17 billion pounds package of tax-payer funded compensation was paid to former slave-owners in Britain. It took British taxpayers 182 years to pay off this debt; indeed, the loan the Government took out to compensate slave owners for the abolition of slavery in 1833 was only repaid in full in 2015.

Enslaved people received no compensation.

Some of the descendants of those owned by British people later became residents in Britain, and through taxation contributed to paying of the debt created by the huge windfall paid to the slave-owners who once owned their ancestors as property.

The legacy of this injustice has been vividly brought to wider public attention by the recent Windrush scandal, which has seen the descendants of enslaved and colonised peoples from former colonies such as Jamaica, many of whom came to Britain to work in the 1950s, deported back to now former colonies many decades after their arrival. See Luke de Noronha’s work on this in Deporting Black Britain’s

Lancaster Cotton Plantation, Guyana

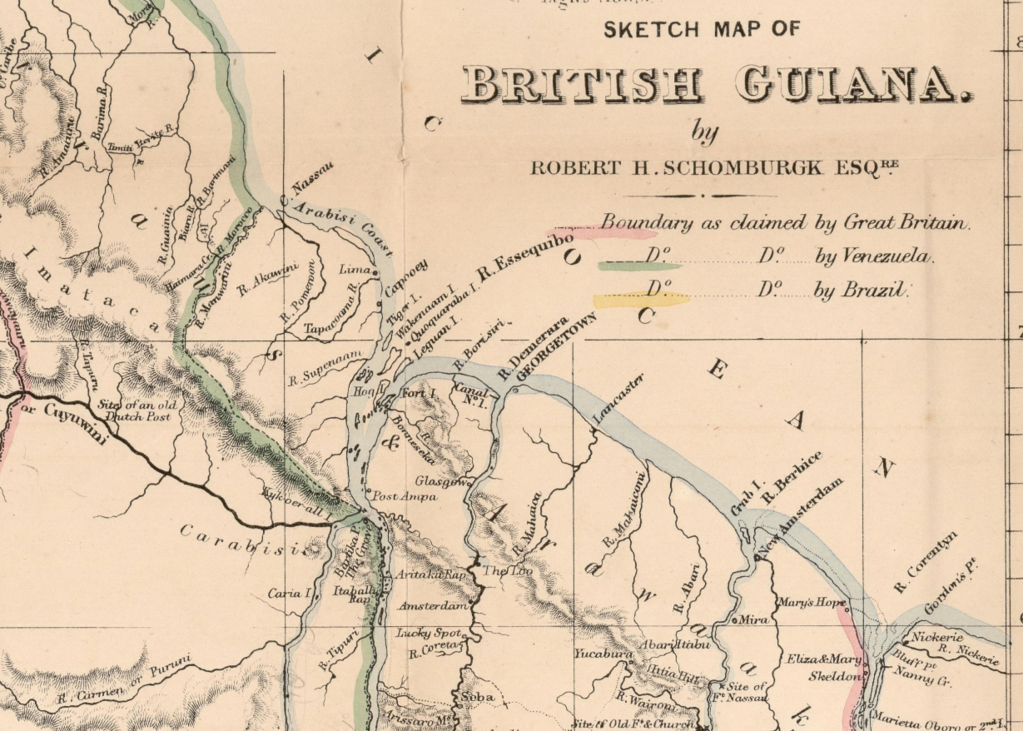

John Bond’s inheritance included a cotton plantation in Guyana called Lancaster. It turns out that there are two Lancaster’s in Guyana, and this Lancaster Plantation was in Demerara, located at the mouth of the Mahaica River (see map below). John Bond’s Uncle Thomas likely came into ownership of the Lancaster plantation in about 1812.

Some 16 years earlier, in 1796, the Lancaster cotton plantation in Guyana was visited by an English physician called Dr George Pinckard. Pinckard described the Lancaster Plantation as ‘distinguished’ by ‘the inhuman treatment of the slaves’. This is a place, he said, where ‘cruelty had become contagious’ and the manager ‘hardened in savage conduct’ and ‘diabolical cruelty’. During Pinckard’s visit an enslaved husband and wife from Lancaster plantation escaped. They were recaptured and flogged. Pinckard is called on to offer medical assistance. When he arrives the man has already died of his wounds, ‘an iron collar’ still fastened around his neck and heavy chains binding his body to that of his ‘almost murdered’ wife. She is in a condition so ‘horrid and distressing can scarcely be conceived’, her ‘flesh’ is ‘so torn as to exhibit one extensive sore, from the loins almost down to her hams’. Pinckard describes this episode as ‘the most shocking’ instance of ‘barbarity’ he witnessed during his journey through the West Indies and South America. Pinckard’s published letters were later used to support the political case for abolition in Britain.

I first came across this reference to the Lancaster cotton plantation on Liam Hogan’s excellent blog, which offers a fuller harrowing extract from Pinckard’s account of this incident .You can also read Pinckard’s book online, note that his account of the Lancaster Plantation is is vol.3.,

While this was still a Dutch colony, by 1760, “British settlers were already in a majority in Demerara, managing plantations for absentee Dutch proprietors. “By 1813, most of the white settlers were British” (Sherridan 2002).

Map of British Guiana by Robert Schomburgk, 1840. This image is an extract of an 1840 map of British Guiana created by Robert Hermann Schomburgk (1804–65), a British naturalist and surveyor known for his pioneering surveys of British Guiana (present-day Guyana). It clearly shows the location of Lancaster at the mouth of the Mahaica River.

In 1815, Josias Booker [the family surname was originally Bowker] (1793-1865) the son of a miller from Over Kellet, a small rural village 10 miles near Lancaster, was employed (likely by Thomas Bond who owned land and property in Over Kellet and would have known the Booker family, or his business partner Thomas Rawlinson, from a branch of the Lancaster Rawlinson family), to work as a plantation overseer in Demerara. By the time of Thomas Bond’s death in 1818, Josias was managing (and acting as attorney) on Bond’s Broom Hall cotton plantation, and had assumed a significant social status in the colony. John Bond inherited a share in the Guyana plantations with Abraham Rawlinson. This Rawlinson was a banker, a partner in Gurneys, Birkbeck and Rawlinson of Fakenham Norfolk, a predecessor of Barclays bank.

John Bond and Abraham Rawlinson were absentee landlords, and Josias Booker appears to have continued to play a central role in the management and development of their overseas plantations for the next decade. In 1829, Josais was awarded a Gold Medal by the London based “Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce’ (which still exists today, known now as the Royal Society of Arts or RSA). Josias’s submission for this prize took the form of a written paper, and testimonials from third parties. It was published by the RSA, and you can read it here.

This gold medal, bestowed under the Colonies and Trade category, was given to Josias in recognition of his work introducing machinery and cattle ‘in aid of slave labour’ on four cotton plantations (Broom Hall, Fairfield, Land of Promise, and Palmyra) in Guyana. Booker had had an Oxen driven plough imported from “near Lancaster” and a Cotton Gin imported from Liverpool to support his improvement works. ‘I have the honour’, writes Booker, ‘of transmitting to you a detailed account of the methods adopted on plantation Broom Hall for the purpose of diminishing human labour in the cultivation of cotton, by the substitution of agricultural machinery and the use of cattle’. His award focused on the increased yields of cotton that Booker stated had been realised through “progressive” agricultural methods. He argued that his methods where driven not only by economic gain, but by a “humane” concern for his enslaved labour force. The evidence to the prize committee of the society, includes a description by Josias of his humane treatment of the enslaved workforce he managed, and his training of neighbouring plantation managers, and enslaved people, in new agricultural practices and technologies –primarily using oxen driven ploughs to increase productivity and yield, and introducing cotton gins. He writes on the introduction of cotton gins:

“Invalids, and children of from ten years to fifteen years of age, after a little practice, would bring 75lbs of clean ginned cotton per day, which is one-third more than the general average of work done in that part of the country by the strongest men in the gangs, with hard labour.”

Booker offers data in the form of accounts of cotton yield over time to support his case of increased yield. His evidence of how this also improved conditions for enslaved people includes alleged testimonies from the enslaved people, ‘our people felt and loudly expressed, the ease they derived from the plough’ and also that he saw an increase in population of enslaved people on the estates he managed, evidence he suggested that enslaved people where living longer and more children where surviving due to his progressive improvements. He suggests that the increased life span was in part because enslaved people now had more time to work on their own small allotments, growing food and raising chickens and pigs.

“The people on this property are comfortably supplied with food and clothing by their respectable owners;* [John Bond and Abraham Rawlinson are named in a footnote as the owners] after the apportioned work of the day is over, it frequently occurs that the industrious have spare time to cultivate their plots of ground, the produce of which, if not given their stock of poultry and pigs, is disposed of for articles of luxury, either in food or clothing. As an encouragement, we prepared the land for them by ploughing and harrowing.”

Josias Booker

There is another side to this increased yields in cotton production on the plantations across the Americas in this period. In The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, Edward Baptist examines the myth that innovations in machine-technology (such as the cotton gin) increased productivity in Southern US cotton plantations in the nineteenth-century. Between 1801 to 1862, the amount of cotton picked daily by an enslaved person in the American South increased by 400 percent. Through a detailed examination of the changing management techniques employed on cotton plantations, Baptist evidences that this increase in cotton production was in fact an outcome of more efficient systems for the exploitation and torture of enslaved pickers. In short, it wasn’t ingenious new machines that were responsible for the spectacular increase in cotton production, rather it an increase in physical violence, combined with meticulous systems of record-keeping, transformed cotton pickers into machines. As Baptist notes, ‘in the sources that document the expansion of cotton production, you will find .. every instrument of torture used at one time or another: sexual humiliation, mutilation, electric shocks, solitary confinement in “stress positions,”, burning, even waterboarding.’

Baptist’s argument, one supported by extensive evidence, that increases in cotton yield did not correlate with better conditions for enslaved workers as claimed by men like Broom, is partially confirmed with an account by Reverend John Smith who arrived in Demerara from England in February, 1817, where he took up a ministry on the Le Resouvenir plantation. In his diary entries from the 1820s, Smith specifically describes cotton plantation workers being “perpetually flogged”, “the whip used with an unsparing hand” and people “confined in stocks” for the slightest infraction.

“Ever since I have been in the colony, the slaves have been most grievously oppressed. A most immoderate quantity of work has, very generally, been exacted of them, not excepting women far advanced in pregnancy. When sick, they have been commonly neglected, ill treated, or half starved. Their punishments have been frequent and severe.”

John Smith

In 1823, Smith was charged with complicity with the Demerara Slave Revolt (see below) for which he condemned to death by hanging. Smith died while in prison. This case caused an outcry amongst the missionary and abolitionist community in Britain. Extracts of Smith’s diary and a transcript of his trial was published and circulated, and the case was discussed in Parliament.

Earlier that same year, 1823, the British Government had decided that slavery should be gradually abolished throughout the British colonies, and “Amelioration Proposals’” [Canning’s amelioration resolutions] were “sent from the British Colonial Secretary to the Governor of Demerara urging that the conditions of the enslaved be improved. The Court of Policy in Demerara examined the proposals on July 21, 1823 and postponed making a decision“. Missionaries were also dispatched to the colonies to report on conditions of the enslaved, including the access of enslaved people to places of Christian worship and rudimentary learning (enslaved people where often banned, for example, from learning to read). differed significantly in particular plantations, but it is particularly notable that Josias Booker includes a reference from a local Wesleyan leader in his submission to the committee, to underscore that the enslaved people in the plantations he managed had access to religious instruction. In short, we might read Josias Booker’s submission to this committee as an attempt, in part to manage the public perception of his character and reputation, and that of the plantation owners, in the face of evidence emerging out of Guyana of the horrific and brutal treatment of enslaved people.

This was then a social and political context characterised by huge contentions over manumission in Demerara and wider British Guiana. In 1826 a group of absentee slave owners and mortgagees of Demerara and Berbice appealed to the Privy Council against provisions for compulsory manumission in the two territories.It is in this heated context, that we need to read Josias Booker’s extremely rosy 1829 account of the lives of enslaved people on the plantations he managed on behalf of Bond and the Rawlinson family.

“The newly wealthy of the new colonies in Britain were not subject to the same personal opprobrium and accusations of depravity as planters resident in the colonies. They were somewhat insulated by distance. As with other absentee owners, they were not themselves directly vulnerable to charges of licentiousness and cruelty. The assault on them by the abolitionists took the form rather of attempts to break down this protection of distance and to undermine their authority to speak on slavery.”

Draper, 2012

Records suggest that planation and slave owner, John Bond, never left Lancaster, UK, or set foot in Guyana, but amidst this growing public scrutiny of absentee “gentlemen landlords”, Booker used his submission to the RSA, to put on the record his own humane record as a plantation manager, while also attempting to protect the reputation and character of the gentleman for whom he worked.

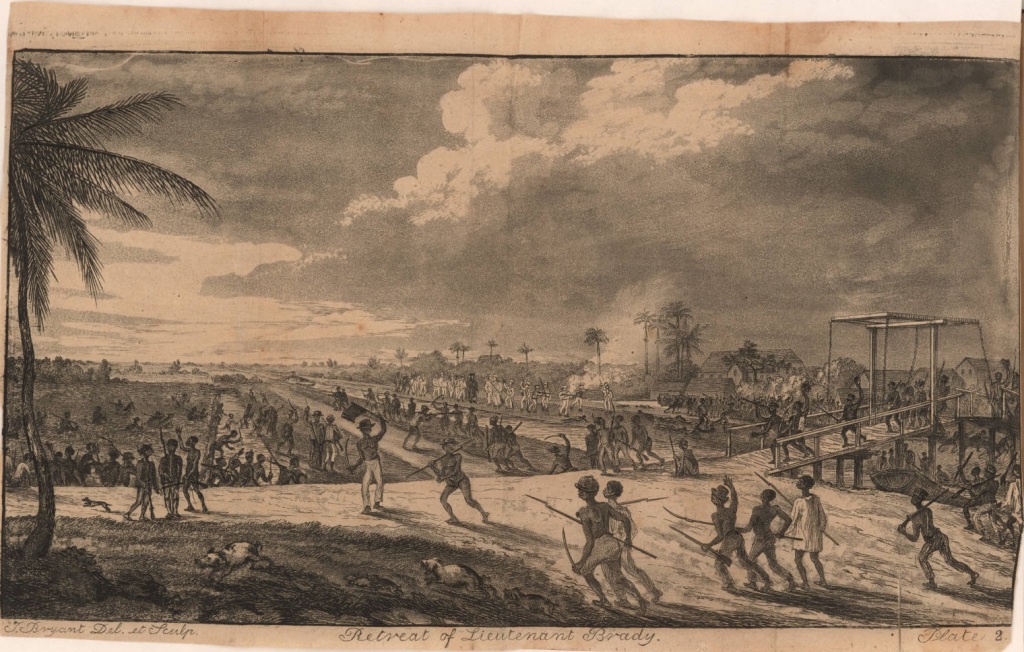

This was also a period also rocked by the rebellions by enslaved people in the colonies. The largest revolt was in Guyana, the 1823 Demerara Slave Rebellion, which involved an estimated 13,000 people, from an enslaved population of 75,000 in Demerara and Essequibo. The uprising began in Demerara the very region in which Booker and his brothers managed the Lancaster and other estates.

“The revolt began on August 18 on the plantation Success, which belonged to John Gladstone, father of future British prime minister William Gladstone. Beginning around 6 p.m. and continuing through the night, the slaves rose to the sound of shell horns and drums. Slaves across the Demerara region surrounded planters’ houses, put overseers in stocks, and seized their guns and ammunition. When the slaves met resistance, they used force—some even commanding their masters’ whips—to fight back.”

Carletta, 2007

Drawing depicting the 1823 Demerara Slave Rebellion which was published in an account of the rebellion written by Joshua Bryant, and published in 1824. (For the purposes of this blog, it is worth noting that George Booker, Josias Booker’s brother who had left Over Kellett, near Lancaster, to join Josias in Guyana, and taken over management of some plantations from Josias who returned to Liverpool in 1827, is listed as a subscriber to this book).

“The white suppression of the uprising was brutally violent. On Tuesday, August 19, there were major confrontations at Dochfour Estate and Good Hope Estate where an estimated 21 Africans were slaughtered by the white military. On August 20 some 300 Africans were massacred at Bee Hive plantation, Elizabeth Hall Plantation and Bachelor’s Adventure plantation.”

Murphy Browne, 2017

Many more of those Afro-Guyanese people who participated in this revolt were executed after they were tried and found guilty. “Ten of the fifty-one slaves who were condemned to death were decapitated and their heads stuck on poles on the roadside” (Sheridan, 2002).

Please read about the contemporary remembrance of this revolt which in 2018 saw a memorial erected in memory of those enslaved people slaughtered in the aftermath of the revolt, now also commemorated on “Demerara Martyrs’ Day” on August 21st each year.

A photograph of the 1823 Demerara Slave Rebellion Memorial, established in 2018 in GeorgeTown, Guyana.

Sir John Gladstone, the MP for Lancaster 1818-1820, and a very significant slave-owner and planation owner in Guyana in the same period, made similar attempts to the Booker’s to manage his public profile in reputation in the context of these rebellions and missionary reports of the atrocities daily committed against enslaved workers by managers and overseers. As Draper notes, the “absentee slave owners of British Guiana .. were conscious of their material interests as a group… and pursued those interests ruthlessly.”

The man who led the slave rebellion, Jack Gladstone, was carpenter/cooper on John Gladstone’s plantation “Success” in Demerara (like many other enslaved people he was given the name of his owner). Gladstone wrote to William A. Hankey, an official of the London Missionary Society, on December 24, 1824, declaring assertions against the mistreatment of slaves on the plantations he owned to be “false and wholly unfounded”

“…my intentions have ever been to treat my people with kindness in the attention to their wants of every description, and to grant them every reasonable and practicable indulgence; these instructions have been strictly adhered to by my Attorney & Manager … therefore, from you and from your Society, I claim that Justice and Protection to which I am entitled”

John Gladstone, 1824 (quoted in Sheridan, 2002)

William Ewart Gladstone, son of John, would be the largest beneficiary from the tax-payer funded windfall which accompanied the abolition of ownership in Britain in 1833. He was paid £106,769 in compensation for the 2,508 people he owned, the modern equivalent of about £80m. William Gladstone’s maiden speech in parliament (June 1833) was in defence of the interests of the West Indian plantation owners, and specifically sought to defend his father’s and his families reputation in the wake of the 1832 Demerara Revolts led by the enslaved Jack Gladstone. He gave this speech in Parliament during the Committee stage of the Emancipation Bill.

Josias Booker and his brothers invested the fortunes they made from the labour of enslaved people in the development of a massive commercial enterprise, a shipping line (the famous Booker Line), an insurance company, and a banking business, as well as expanding in their Guyana plantation holdings – indeed the influence of this family in shaping the history of the colony over the following one hundred years cannot be understated. While in 1830, Josias Booker claimed to have ‘no interest in West Indies property’ describing himself as “merchant and shipowner in Liverpool, and chairman of the Royal Insurance company and Royal Bank“, records show Josias and his family remained planation owners in then British Guiana. For example, the family retained ownership of the Broomhill plantation, while the enslaved people who lived and worked on it, and the Booker brothers submitted several claims for compensation for the enslaved people their owned, in 1833. “The Booker brothers and their associates collectively submitted claims on 52 slaves, giving their fledgling business a cash injection of what amounts to 317,240 pounds (about $418,000) in today’s currency, according to archives.” (Hopkinson, 2017).

Emancipation provided the Booker’s with an opportunity to extend their unpaid labour force and land holdings. As Natalie Hopkinson writes:

“Because many British Guiana planters used abolition of slavery as an opportunity to liquidate their human assets and get out of the sugar business, the Booker brothers were able to acquire them cheaply. Their enslaved work force grew to 315 people in the period immediately following emancipation. After squeezing the workers for four more years of unpaid labor, on Aug. 1, 1838, at the appointed time, the Booker brothers manumitted them.”

Natalie Hopkinson

The Booker family soon came to hold a monopoly in sugar plantations in the colony, before selling their holdings to a partner, McConnell, in the 1880s.

Josias Booker, based in Liverpool from 1827, invested his energy, time and resources in civic projects, such as the Blue Coat Hospital in Liverpool (Governor and Trustee), and in the building of a church, St Anne’s Church, Aigburth, where he was buried in 1865. His story reveals how profits from slave business financed the industrialisation of England and the development of its civic infrastructure, religious and welfare estate.

You can read more about the incredible rise of Josias Booker and his brothers from Over Kellett, here (written by the Liverpool historian Laurence Westgaph), here (written by Ben Richardson, author of a recent book on Sugar -2015), this history of the Booker Shipping Line later established by the brothers, and Judy Slinn and Jennifer Tanburn’s official company history of the Booker business empire, The Booker Story (2003).

The name Booker is perhaps most famous today from the literary prize they helped found, the Booker Prize, formerly known as the Booker–McConnell Prize (1969–2001) and the Man Booker Prize (2002–2019). When the writer John Berger was awarded the Booker Prize in 1972, for his fiction novel G, he gave a speech in which he made drew links between the historic role of the Booker company in the exploitation of generations of people in the West Indies and Caribbean, and the persistent and enduring poverty and exploitation in the region today. As Berger stated:

“As a revolutionary writer, to share this prize with people in and from the Caribbean, people who are involved in a struggle to resist such exploitation and, eventually, to expropriate companies like Booker.”

John Berger – see the text of his speech here links and footage here.

As Nick Draper notes:

“The resonance of the pre-emancipation period of prosperity for British Guiana and of the accumulation of wealth by slave owners there did not fade away in the later nineteenth century. The history of Booker McConnell, the firm that kept a vice-like grip on Guyana’s sugar industry until nationalization in the 1970s, exemplified these continuities between pre- and post-emancipation. The firm, forged in the twentieth century, brought together: (1) the firm founded by the Booker brothers, who were largely managers of other men’s slaves in the 1830s, but who had, by then, also accumulated sufficient capital in the colony under slavery to establish the respective firms of Josias Booker in Liverpool and George Booker in Georgetown, and to take advantage of the disruptions of emancipation; (2) the Campbell family, descendants of John Campbell Senior, the Glasgow merchants and large-scale slave owners; and (3) the firm developed by Quintin Hogg, the founder of both the Regent Street Polytechnic and the dynasty of Tory politicians that includes the First Viscount Hailsham (Lord Chancellor in 1928–9 and 1935–8), the Second Viscount Hailsham (later Lord Hailsham and Lord Chancellor in both the Tory government of Edward Heath [1970–4] and that of Margaret Thatcher [1979–87]), and the former MP and minister, the Right Honourable Douglas Hogg.”

Nick Draper

“I am [still] the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea”

In Guyana, some of the plantations owned by the Bond and Rawlinson families, such as plantation Albion, still exist today. In 1976, the government of Guyana nationalised and merged the sugar estates operated by Booker Sugar Estates Limited and Jessels Holdings to form the Guyana Sugar Corporation Inc., also known as GuySuCo. The Albion Sugar Estate (which amalgamated several older estates including Lancaster) is one of the largest sugar production estates, extending over 50 square miles with circa 20 acres of sugar cane under cultivation. It’s sugar processing factory has a grinding capacity of 170 tonnes cane per hour, and the whole enterprise employs around 4000 people.

While I was researching this blog, workers at the Albion sugar estate protested the conditions in which they where working in the context of the Covid-19 virus, and went on a one-day strike in support of a colleague who was sacked for speaking to the media about unsafe working conditions. See more on conditions for sugar plantation workers here.

An aerial photograph of the Albion Sugar Estate today, from the company website.

As the American novelist and essayist James Baldwin reminds us, the history of slavery is the history of capitalism, and it remains, ‘literally present in all that we do’.

Or as the Jamaican born Sociologist Stuart Hall put it:

I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea. I am the sweet tooth, the sugar plantations that rotted generations of English children’s teeth. There are thousands of others beside me that are, you know, the cup of tea itself … Because they don’t grow it in Lancashire, you know …Not a single tea plantation exists within the United Kingdom. This is the symbolization of English identity – I mean, what does anybody in the world know about an English person except that they can’t get through the day without a cup of tea? Where does it come from? Ceylon – Sri Lanka, India. That is the outside history that is inside the history of the English. There is no English history without that other history.

Stuart Hall

Lancaster Secondary School, in Demerara-Mahaica today

How to cite: Imogen Tyler (2020) ‘Black Lives Matter and Legacies of Slave Ownership in Lancaster: the Bond’s and the Booker Brothers in Guyana’ [website]

This is a brief sample of some of the research I have been doing on Lancaster’s historical links with slavery. A little of this work found its way into my recent book, Stigma: the Machinery of Inequality.

The preliminary research forms the basis of an ongoing project on Decolonizing Lancaster, which I have been working on for some years, but am sharing pieces from in the unpolished form of blog posts, due to local interest in Lancaster’s links to slavery, including the formation of a local black history group of which I am honoured to be member, and work with the local city council and local schools.

This broad project which seeks to illustrate how we can do local history in ways which are reparative, and in doing make visible important but often hidden global legacies and connections between inequalities and injustices in the past and the present.

Further blog posts will be forthcoming on these themes.

References and Further Reading

Abstract of the Report of the Lords Committee on the Condition and Treatment of the Colonial Slaves (1833)

Analysis of the Report of a Committee of the House of Commons on the Extinction of Slavery, with Notes by the Editor (1833) London : Printed for the Society for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Dominions.

Bahadur, G. (2013) Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture

Baptist, E. (2016) The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism.

Beckles, H. (1994) “The Colours of Property: Brown, White, and Black Chattles and their Responses on the Caribbean Frontier,” Slavery and Abolition 15

Brown, M. (2017) AUGUST 18-20, 1823 ENSLAVED AFRICANS AND AN UPRISING IN DEMERARA, GUYANA (blog post)

Brown, R. (2017) Surviving Slavery in the British Caribbean

Bryant, Joshua (1824). Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August 1823

Carletta, D. M. (2007). Demerara, revolt. In J. Rodriguez, Encyclopedia of emancipation and abolition in the transatlantic world. Routledge.

Costa, E. V. da, (1994) Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823.

“In Crowns of Glory, Emilia Viotti daCosta tells the riveting story of this pivotal moment in the history of slavery. Studying the complaints brought by slaves to the office of the Protector of Slaves, she reconstructs the experience of slavery through the eyes of the Demerara slaves themselves.”

Checkland , S.G. (1971). The Gladstones: A Family Biography, 1764–1851 , Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Checkland, S. G. 1954. “John Gladstone as Trader and Planter.” The Economic History Review 7 (2): 216–229.

Craton, M. (1982) Testing the Chains: Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies Ithaca: Cornell University Press,

Daly, V. T (1975) Short History of Guyanese People

Draper , N. (2010) The Price of Emancipation: Slave-Ownership, Compensation and British Society at the End of Slavery . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press ,

Draper, N. (2012) ‘The rise of a new planter class? Some countercurrents from British Guiana and Trinidad, 1807–33’, Atlantic Studies, 9:1, 65-83.

Dresser, Madge, and Andrew Hamm, eds. 2013. Slavery and the British Country House. Swindon: English Heritage.

Drew, Samuel. (1824). MEMOIR OF THE REV. JOHN SMITH, LATE MISSIONARY IN DEMARARA, THE MARTYRED VICTIM OF LEGAL PERSECUTION. The Imperial Magazine, 6(65), 400-415.

Eltis, D. (1972). The Traffic in Slaves between the British West Indian Colonies, 1807–1833. Economic History Review, 25(1): 55–64.

Hall, C. Draper, N., McClelland, K., Donington, K., Lang, R., (2014) Legacies of British slave-ownership: colonial slavery and the formation of Victorian Britain

Hall, Catherine. 2011. “Troubling Memories: Nineteenth Century Histories of the Slave Trade and Slavery.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 21: 147–169

Also watch Britain’s Forgotten Slave-owners, a two-part BBC programme based on this research, presented by David Olusoga, originally broadcast in July 2015

Hochschild, A. (2006). Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hopkinson, N. (2017) Booker Prize’s Bad History

Ishmael, O. (2013) The Guyana Story: From Earliest Times to Independence

Josiah, B. P. (1997). After Emancipation: Aspects of Village Life in Guyana, 1869-1911. The Journal of Negro History, 82(1), 105-121.

Palmer, C. (2010) Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power: British Guiana’s Struggle for Independence, University of North Carolina Press.

Matthews, G. (2003) Caribbean Slave Revolts and the British Abolitionist Movement: A Memoir (Antislavery, Abolition, and the Atlantic World)

Mc Gowan, W. (2018) A Survey of Guyanese History: A Collection of Historical Essays and Articles by a Guyanese Scholar.

Moohr , M. (1972) “The Economic Impact of Slave Emancipation in British Guiana, 1832–1852” . Economic History Review 25 , no. 4 : 588 – 607

Nichols, John. (1824). REV. JOHN SMITH. The Gentleman’s Magazine: And Historical Chronicle, Jan. 1736-Dec. 1833, 281. Proceedings before the Privy Council against Compulsory Manumission in the Colonies of Demerara and Berbice. (1827). London.

J. Moyes Rodney , W. (1979). Guyanese Sugar Plantations in the Late Nineteenth Century: A Contemporary Description from the “Argosy”

Rodney, W, and Lamming G. (1981) A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905

Rugemer, E. B. (2018). “Chapter 7: The Political Significance of Slave Resistance”. In Slave Law and the Politics of Resistance in the Early Atlantic World. Cambridge (MA): Harvard

Sheridan, Richard (2002) “The Condition of the Slaves on the Sugar Plantations of Sir John Gladstone in the Colony of Demerara, 1812–49.” New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 76 (3): 243–269. University Press

Slinn , J, and Tanburn, J. (2003) The Booker Story . London : Jarrold for

Booker. Smith, J. (1824) The London Missionary Society’s Report of the Proceedings Against the Late Rev. J. Smith, … who was Tried Under Martial Law, and Condemned to Death, on a Charge of Aiding … in a Rebellion of the Negro Slaves, from a … Copy Transmitted to England by Mr. Smith’s Counsel … With a Appendix, Etc

Williams, E. (1944). Capitalism and Slavery .

Williams, E. (1984) From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean 1492-1969

See here for historical journals from Guyana – digitised.

Leave a comment