Harris Wood & Jonny McDowell (Sixth form students at Lancaster Royal Grammar School)

Minerva Road is the name of a street on the Lune Industrial Estate in Lancaster (see street sign below and map of area the street is in). There have been many British ships and vessels named Minerva (name to the Roman goddess of wisdom) and therefore we have conducted research into whether this street was named after a Lancaster built vessel. Our research focused on ships built and launched from Lancaster, including those involved in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and in direct trade with the West Indies. Using the slave voyages database, we identified several 18th century ships called Minerva with connections to Lancaster.

The first of these ships, Minerva I sailed to the African coast in 1758. This voyage was led by Captain Preston, who bought 250 enslaved people, likely from the Windward/Guinea Coast, where he and other Lancastrian slave-traders held contacts and agents (see Elder, p.57). This voyage took place during a period of great military turmoil between Britain and France, the seven years war. Consequently, whilst carrying over 200 enslaved people to Antigua, Minerva I and the people it carried was plundered by French privateers. Dr Nicholas Radburn suggests that once its valuable cargo was plundered, and the fittest enslaved people onboard taken as the ‘prize’, the ship itself was likely set loose and taken by Preston into port of Saint John in Antigua. Certainly, Captain Preston survived this trip and would later captain other Lancaster Slave ships.

In the most significant study of Lancaster’s relationship to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, Slave Trade and the Economic Development of 18th-Century Lancaster (1992), the historian Melinda Elder details a will and letter from a man called John Scovern, dated May 1. 1760, who worked and likely lived as a resident slaver on the Windward Coast of West Africa –an area preferred by Lancaster Slave traders, who specialized in smaller ships which could make faster round-trips and could access more inaccessible areas of coast. Scovern’s will and letter is interesting as it mentions Captain John Preston, and may well of been brought back to North West England by him to, where it was proved.

“I John Scovern at present on the Windward Coast of Africa, being very sick in body, but of a sound and disposing mind and memory make this my last will and testament … my effects after they are valued I leave to the care of Captain John Preston from Lancaster as my sole executor … I desire Bento, a girl slave to be carried to the West Indies and 4 slaves to be given her out of my stock, I leave William Tydeman 2 slaves, to Sarah Tinder 2 slaves, to my executor Captain John Preston, for his trouble, 8 slaves.”

Elder, 1992, p.57

This will also reveals evidence of more personal and intimate relationships between Lancashire slavers and the people they ruthlessly exploited, enslaved and sold. We don’t know what the relationship was between John Scovern and the girl Bento, perhaps a domestic slave he has formed an attachment to, perhaps his daughter? It also reveals that Preston is a slave owner, like many slave ship captains.

Elder further reveals that Captain Preston had sailed to Africa three times by this date, once in the Minerva I in 1758 and twice in the Thetis I in February and December 1759. This latter voyage would have accounted for his presence when John Scovern wrote his letter. No doubt Preston had dealt with him on his earlier voyages. As it turned out Captain Preston’s own will was being proved just two years later. He, too, died in Africa on a slaving voyage to Sierra Leone in 1762.

Minerva II was built in Chester in 1748 and then registered some years later in Lancaster, in 1765. The vessel was owned by Caton born slave trader Thomas Hinde.

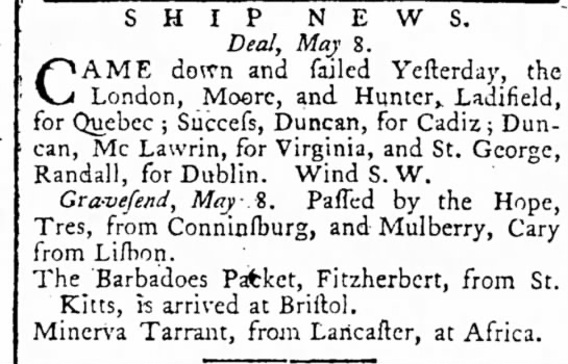

Whilst records of Minerva II’s voyages are sparse, we discovered it conducted at least one slave voyage in 1765, departing from Lancaster’s River Lune Quay on 11th of January. Four months later, the arrival of the Minerva in Africa was recorded in the London press shipping news –see advert below which reports Minerva, Tallon (not Tarrant as reported in newspaper below which is a misspelling) – Captain- from Lancaster is now at Africa. On its middle passage the Minerva carried 210 enslaved people and 12 crew members from an unspecified area of the West coast of Africa (though likely somewhere on the Gulf of Guinea/Sierra Leone area where Lancaster slave traders did a lot of business in this period). The middle passage saw the death of 30 enslaved people. Only 180 enslaved people of the original 210 then disembarked in Kingston, Jamaica on 26th October 1765. Here, they were to be sold at the Jamaican slave market. Now emptied of people, the hold of the Minerva would then have been filled with goods (such as mahogany, rum, sugar) the majority of which would have supplied Lancaster merchants. Minerva II stayed in Jamaica until April 1766, arriving back in Lancaster in July 1766.

Minerva III built Lancaster 1782, 150 tons “owned by William Thompson and John Coupland (or his executor by 1786), sailed under various captains (named) to St Lucia, St Vincent and Jamaica – reported lost c 1791. Not a slaver but a West Indies trader” (information from Mike Winstanley and Melinda Elder via email Jan 2021).

Minerva IV built in Lancaster 1795, owned by Thomas Jackson and George Danson (by 1797 just Danson), 185 tons, sailed out of Lancaster. “The Manchester Mercury 27 Oct 1795 has her return to Lancaster from St Thomas with sugar, mahogany, cotton and tortoise shell for G. Danson and smaller cargo for T. Jackson.” She was sold to new Liverpool based owners c1801 and became a slave ship working out of Liverpool. (information from Mike Winstanley and Melinda Elder via email Jan 2021).

Minerva IV’s first transatlantic slave voyage took place in 1802.i231 people were enslaved on the ship at Bonny in Nigeria before being transported to the Bahamas. This voyage saw the death of 19 of those enslaved people. The 212 who survived were disembarked from the vessel, and would have been sold at a slave market in the Bahamas. Following this, Minerva IV took a minimum of 4 further voyages until 1807, transporting similar numbers of enslaved people from one continent to another. One advertisement for sale of enslaved people from a 1806 slaving voyage by the Minerva IV to Demerara reads:

“The Subscribers will expose for Sale, on Friday next, the 14th instant, at the Store of Messrs. J. Madden & Co. under the Formalities prescribed by Law, 190 prime Windward Coast Slaves, Imported in the Ship Minerva, Capt. Stowell.”

Demerary, Oct. 10, 1806. C. M acrae. H. L. Underwood.

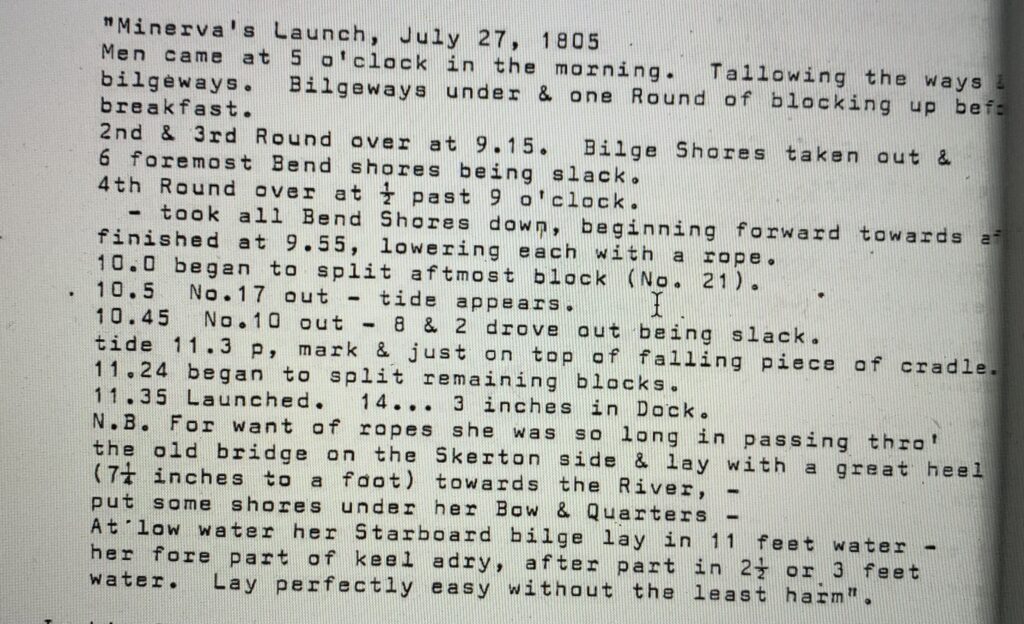

Finally, the Minerva V which was launched from Lancaster in 1805. she was 551 tonnes, took 14 months to build, and was said at the time to be the largest ship ever built in Lancaster. She cost her buyers over £7200. The launch of a ship was a big event at a shipyard, and in a city as small as Lancaster everybody would have been aware, and many involved in the activity and celebration. The ships owners, and local important merchants and/or dignitaries, would be invited to a special dinner to launch the vessel, and celebrations would have also taken place amongst the workmen (and women) in the shipyard. No doubt crowds would have formed on the banks of the River Lune to watch the careful process of floating the ship into the river using the high tide. This was likely particularly true of the launch of the 1805 Minerva, as it was the biggest vessel ever built by John Brockbank -Brockbanks ship yard which was on the site of Sainsbury’s city centre car park today. In his daybook John Brockbank describes the technical aspects of the launch of the Minerva on JuIy 27, 1805, a process which begins at 5am and ends with the ship floated and launched at 11.35am.

The Minerva V was not involved in transatlantic slavery but traded across central and south America until 1811. It spent most of its time transporting convicts to Australia – once to Van Diemen’s land (now Tasmania) and thrice to New South Wales. Some of those transported on the Minerva at been convicted at the Lancaster Assizes. We can find out a little about these convicts from the following online records, from entries in the British convict transportation registers 1787-1867 database compiled by State Library of Queensland from British Home Office records. Hundreds of people were sentenced to transportation in the Courts at Lancaster Castle. Lancaster Castle website has records of those transported, often in lieu of a sentence of hanging.

Amongst the Lancaster transportation records are those of children, such as Elizabeth and George Youngson, transported in 1788 for theft. While this blog post describes the process of transportation from Lancaster Castle through an account of three members of the same family, Mary Storrs, Ellen Storrs and Edward Storrs of Melling parish , Lancashire, who are sentenced to transportation for stealing milk in 1801.

What these five Lancaster built ships reveal is the significant role that Lancaster played in both the transatlantic trade of enslaved people and plantation goods as well as the deportation of convicts to Australia in the 19th Century. As Imogen Tyler writes:

“Lancaster was one of the major judicial centres for the sentencing to transportation of convicts to colonial outposts during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While Lancaster slave traders shipped branded Africans as chattel across the Atlantic, Lancaster’s judicial elites* branded and transported the English poor to North America, the West Indies, and, after the American War of Independence, to Australia. For a period, then, Lancaster was a small but significant global headquarters for the forced movement of unfree labour across the world.”

Imogen Tyler, Stigma, 2020

*These elites would have been either circuit judges appointed by central government who toured counties twice a year dealing with serious crimes from all over Lancashire at the assizes, or justices of the peace from an area which included the whole of the South Lonsdale and Lancashire North of Sands, sitting at Quarter Sessions.

The unique stories of human suffering on board each of these Lancaster-linked Minerva ships, highlights the sacrifices of human life which were behind at least some of our local history of successful commerce in the 18th century. This offers a different understanding of Lancaster as an important player in the transatlantic slave trade, plantation economies and transportation to new colonies such as Australia, and invites us to question the possible histories of other street names, local sites and monuments.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Harris Wood and Jonny McDowell, sixth form students LRGS. Edited by Isabella Tyler and Imogen Tyler, with additional historical input from Dr Nick Radburn, Professor Imogen Tyler, Dr Micheal Winstanley and Dr Melinda Elder. This blog was written as part of our series with students from local schools in Lancaster.

HOW TO CITE

Harris Wood and Jonny McDowell (2021) A Lancaster street called Minerva and four Lancaster ships calls Minerva, Lancaster Slavery Family Trees (Blog), available at https://lancasterblackhistorygroup.com/2022/11/25/a-lancaster-street-called-minerva-and-four-lancaster-ships-called-minerva/