Travis Taylor & Isabella Tyler (Sixth form students)

We are living in the aftermath of Trans-Atlantic slavery. The enslavement and indenture of people continues today in modern forms of slavery. Often viewed as an historical abomination, the threads of slavery have been long-woven, and its influence can still be found and felt in our modern societies. Despite the UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948) recognising all people as equals, the legacy of slavery – be this racism, the restriction of liberty or even the ownership of humans by others– is far from eradicated.

As part of the Lancaster Quay Heritage Project, a small group of Sixth Form students from both Lancaster Royal Grammar School and Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School have researched and discussed Lancaster local history and connections to the slave trade with Professor Imogen Tyler (Head of Sociology at Lancaster University) and Dr Sunita Abraham (Researcher at Lancaster University), alongside Mr Jamie Reynolds (History department at LRGS), all of whom are members of the Lancaster Black History Group. Our current project puts forward an enquiry into the naming of the streets at the Redrow Housing Estate upon New Quay (a housing estate developed mid 2010’s), and the neighbouring Lune Industrial Estate (developed on the site of a former Mill in 1970s). This investigation is evidence-led and aims to uncover and discuss the interwoven histories that are perhaps uncomfortable to recognise as crucial in the Lancastrian historical narrative.

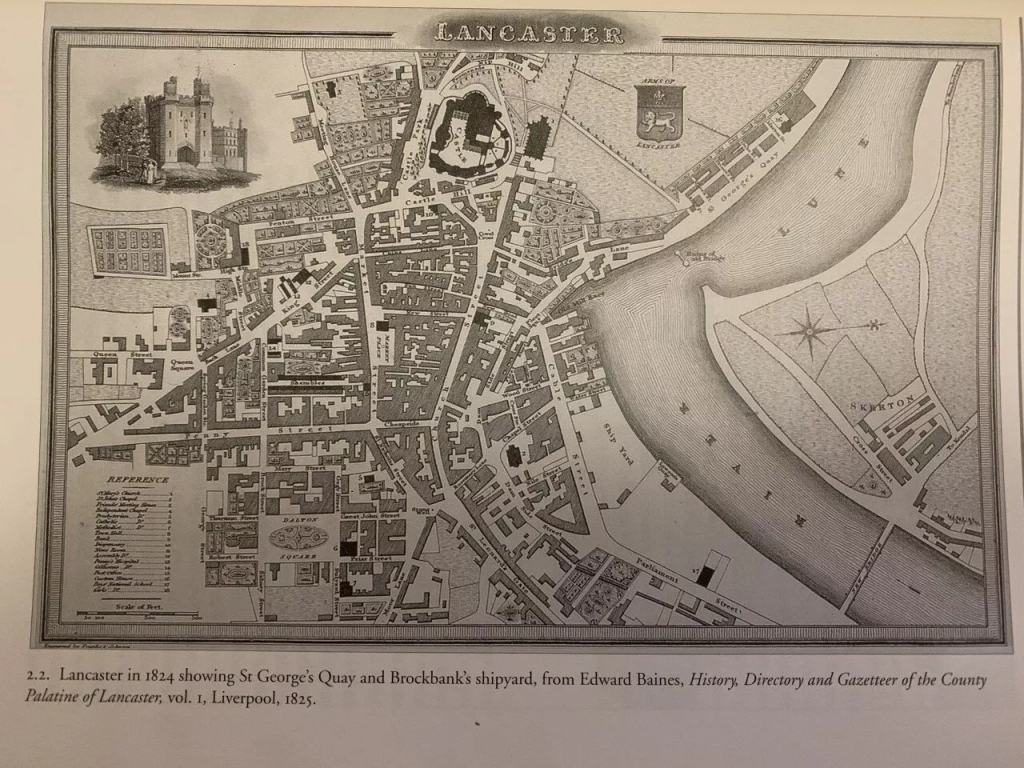

In the 18th century, Lancaster was a significant shipbuilding port in the North West of England ships. These ships were used in a wide array of trades, the transportation of goods around costal ports, between England, Africa, and the West Indies and Americas; the coasts of colonies of an expanding British Empire, but some were used in the Trans-Atlantic Slave trade as part of the infamous triangular trade. There were several shipbuilders in Lancaster, but one the most successful was Brockbank’s which began as a shipyard in 1738, a family run initially by two brothers, John and George Brockbank. This company were responsible for the building and launch of over 100 ships from Lancaster Docks between 1738 and 1801 (see David &Winstanley, 2013). A number of these ships which were captained by Lancastrian slave traders such as Robert Dodson, John Preston and Thomas Hinde. Brockbank’s yard was based on Green Ayre, on Cable Street, which is now the site of a Sainsbury’s supermarket and its carpark. As a group, we have taken particular interest in the names of the vessels crafted and issued by Brockbank’s, which include Ceres, Europa, Minerva, Paragon and Thetis. All of the above – in addition to Brockbank itself – are registered street names within the Lune Industrial Estate. Our project is concerned with thinking about and making visible the histories and human tales of injustice relating to these street names. Not least, as many 18th century Lancaster merchants made their fortune on the back of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Brockbank Avenue is a street on the Lune Industrial Estate. The Brockbank family lived in Lancaster, directly opposite the shipyard. Their work widely accelerated Lancaster’s influence as a significant UK 18th century merchant port. Their ships are recorded to have docked in various coasts of West Africa, and smaller provinces such as the West Indies; areas abundant in cotton and sugar plantations, and sources of exotic woods such as mahogany.

Robert Gillow of ‘Gillow & Co.’ was an important Lancaster furniture business in the 18th century, and a significant national furniture maker who pioneered the use of exotic woods in high end furniture making and design. You can read more Gillows and see an example of their work, the Ladies Box (1808), here. The Gillows relied on merchants, some using locally built ships, to import exotic woods for their fine furniture works in Lancaster as well as rum, sugar and other profitable plantation goods. Gillows also used their merchant networks to export furniture for colonists to purchase in the New World and colonies. (New evidence from historians Melinda Elder and Susan Stuart reveal that Gillows also had 1/12 shares in one Lancaster slave ship, the Gambia, captained by Robert Dodson).

“Some Lancastrians lived and worked as merchants and plantation owners in the West Indies, and had direct involvement with the slave trade or used slave labour. Having Lancastrian connections in the West Indies made it easier for Lancaster based merchants, such as Gillows, to trade at such a distance.”

The influence of the Brockbanks and other Lancaster shipbuilders, extended further than their production of ships, playing a significant part of a local economy, in supporting local trades required to fit out the ships, such as blacksmiths, and even gunpowder works. George Brockbank’s wife Mary, and daughter produced the sails for Brockbanks vessels, and the sail making arm of Brockbanks became a substantial business in its own right which Mary continued after her husband death. The combined efforts of the Brockbank family reveals the economic opportunities provided by Transatlantic Slavery and direct trade with the West Indies (newly established plantation colonies, many slavery-based societies), which was seized upon by many families and the wider Lancastrian community. This age of sail and commerce saw a new wealth pour into Georgian Lancaster, whilst across the ocean enslaved people and the profits of their labour were enabling this growth of a wealth and investment.

Our reassessment of our home city of Lancaster, as a city which grew in size, wealth and importance in the 18th century upon the Transatlantic trade and the wider direct trade with West Indies slavery-based economies, from the felling of Mahogany trees in the Caribbean, to establishment of Sugar Plantations in the British Virgin Islands and beyond, has been challenging.

We are living in times of reparative history. Statues of political figureheads are being toppled and uprooted from a national history rich in racial prejudice and oppression. Revisiting the legacies of shipbuilders such as the Brockbanks is important work to renew our understanding of local history. There are obvious tensions between a desire to celebrate the respected craftsmanship of Brockbank’s vessels and not obscuring some of the darker motivations and human atrocities committed behind the construction of some vessels. The local street name “Brockbank Avenue” commemorates the work of these local shipbuilders. As a community, we feel it is our responsibility to recognise all dimensions of this craft and trade, including some of the more abhorrent events that took place aboard Lancastrian built slave vessels, captained and crewed by Lancastrian men. We hope to make this once concealed history more visible through our project.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Written by Travis Taylor, Lower Sixth Form student, LGGS and Isabella Tyler, Upper Sixth Student, Lancaster Girls Grammar School. Edited by Imogen Tyler with historical input from Melinda Elder, Michael Winstanley.

How to cite

Travis Taylor and Isabella Tyler (2021) Building slave ships in Lancaster: Brockbank shipyard and Brockbank Avenue, Lancaster Slavery Family Trees (Blog), available at https://lancasterblackhistorygroup.com/2022/11/25/building-slave-ships-in-lancaster-brockbank-shipyard-and-brockbank-avenue/